Inflation tax

Inflation tax is a term which refers to the financial loss of value suffered by holders of cash and fixed-rate bonds, as well those on fixed income (not indexed to inflation), due to the effects of inflation. This financial loss of value is often expressed as a loss of purchasing power. It may be better characterized as a wealth transfer than a tax - since many people including debtors, holders of hard assets and some equities may simultaneously gain. Many economists hold that inflation affects the lower and middle classes more than the rich, as they hold a larger fraction of their income in cash, they are much less likely to receive the newly created monies before the market has adjusted with inflated prices, more often have fixed incomes, wages or pensions, and lack the means to avoid domestic inflation by reallocating assets overseas. Some argue that inflation is a regressive non-linear consumption tax. [1] Nevertheless, inflation improves the economic position of people with outstanding fixed interest debt like student loans and mortgages. It can improve the nation's balance of trade - stimulating exports with a less expensive currency - and decreasing imports. A large portion of the "tax" also falls on foreign holders of fixed income debt in the inflated currency. It is important to note that this "tax" on creditors is coupled with a simultaneous transfer to debtors - reducing their debt burden. By transfering wealth to people who are more likely to spend it, an inflation "tax" can further increase real (inflation adjusted) economic growth (beyond its beneficial impact on trade). It may also hasten new purchases since inflation makes it costly to keep cash. Inflation can increase liquidity in depressed real estate markets since it would increase nominal asset values back above the loan values. This improved LTV allows for people to sell their homes, and move to pursue better economic opportunities and as such can improve efficiency of the labor markets. In this way, an "inflation tax" can improve real (inflation adjusted) economic growth and improve employment. Therefore a very tight monetary policy which seeks to reduce inflation - even at the cost of real (inflation adjusted) economic growth and jobs can be viewed as a "stagnation tax".

Contents |

How it occurs

When central banks print notes and issue credit, they increase the amount of money available in the economy. This is sometimes done as a reaction to worsening economic conditions. It is generally held that in the long run, an increase in the money supply causes inflation. Some have argued that, in effect, increasing the money supply and causing the holders of money to pay an inflation tax is a form of taxation.

If the annual inflation rate in the United States is 5%, one dollar will buy $1 worth of goods and services this year, but it would require $1.05 to buy the same goods or services the next year; this has the same effect as a 5% annual tax on cash holdings, ceteris paribus.

Governments are almost always net debtors (that is, most of the time a government owes more money than others owe to it). Inflation reduces the relative value of previous borrowing, and at the same time it increases the amount of revenue from taxes. Thus it follows that a government can improve the debt-to-revenue ratio by employing inflationary measures.

However, if the government continues to sell debt, by borrowing money in exchange of debt papers, these debt papers will be affected by inflation: they will lose their value, and therefore they will become less attractive for creditors, until the government will not find any willing to buy debt.

An inflation tax does not necessarily involve debt emission. By simply emitting currency (cash), a government will induce liquidity and may trigger inflationary pressures. Taxes on consumer spending and income will then collect the extra cash from the citizens. Inflation, however, tends to cause social problems (e. g., when income increases more slowly than prices).

"Tax on the inflation tax"

Although not meant by the term "inflation tax", a related effect is the tax on interest and investment "income" when the tax is levied against the nominal interest rate or nominal gains.

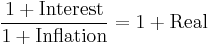

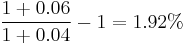

For instance, if someone buys a bond with a nominal interest rate of 6% and the rate of inflation is 4%, their "real" interest is 1.92%.

If, however, they are taxed 25% of the 6% interest "income", or 1.5%, this can be thought of as composed of a tax on real income (0.5%) and a tax on inflation (1.0%). The same principle applies to capital "gains" taxes not adjusted for inflation. In any case, this "tax on the inflation tax" is essentially equivalent to a tax on holdings ("wealth tax") equal to the nominal tax rate times the inflation rate (in example above, 25% of 4% inflation equals 1.0%.) This "property tax" can even apply to non-monetary assets as well as money earning interest. Thus, money itself is subject to both the inflation tax and the tax on the inflation tax, while other assets, on which nominal profit or gains taxes are imposed, are subject only to the tax on inflation.

Another negative effect of this tax is that even inflation-indexed bonds carry inflation risk, as the inflation compensation is taxed.

Negative interest rates

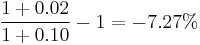

If there is a negative real interest rate, it means that inflation is more than the interest. Suppose if the Federal funds rate is 2% and the inflation rate is 10%, then it means that the borrower would gain 7.27% of every dollar borrowed.

This may lead to malinvestment and business cycles, as the borrower experiences a net profit by repaying principal with inflated (devalued) dollars.